The theoretical nuclear shape data is ready to be connected to molecular probability theories. The Static Nucleus Theory is deterministic and electron orbital clouds are not. A blind spot in physics is being highlighted by my theory. The nanometer scale is photographed with difficulty and femtometer nuclei are far too small to record their shapes, but certainty about a quark is announced routinely. The gap in knowledge between atomic scale and quark scale was neglected. A million is the size of the dark scale. The old nuclear shape theories are still used from decades ago about liquid drop nuclei or helium clusters building heavier nuclei. Today’s researcher follows no authoritative decision about whether protons and neutrons swarm dynamically or if the nucleus has a fixed configuration of nucleons. Now that a static nucleus theory is established, molecular electrons can theoretically be connected to nuclear protons with deterministic flux. Two lines of flux wrap around each other to make a chemical bond. Quark theory can be neglected without any impact on scientific progress in chemistry, physics, lasers, biology, fusion, superconductors, global warming or fission.

Metal definition from the mirror effect, Non-metal definition

A metal gives a reflection that is from the direction of a proton.

A non-metal gives a reflection that is probably from the direction of an electron.

This definition is independent of electrical conduction. For metals, the quasi-immobile nuclei make the famous mirror surface reflection. For non-metals, the mobile electrons probably make a blurred, non-mirror reflection. Electrons are linked to protons to make discrete pairs (paper #12 Fig. 2 and 5). Photons are absorbed and emitted from a flux linking an electron to a proton. The center of a proton has a mirror. Disregard quarks. The center of an electron has a mirror. This is part of the Theory of Enough. It theorizes a cosmology of the solid state.

Most chemical elements are metals. Electrical conduction of non-metals is a subtler phenomenon than the mirror properties of non-metals. Electrical conduction of metals is a subtler phenomenon than the mirror properties of metals. Indium tin oxide is a conductor and it is a non-metal. Indium tin oxide is a common transparent commercial wiring product. InSnO is a non-mirror non-metal that conducts electricity. That alloy is consistent with my theory that features mirrors.

The malleability of metals is easy to notice. Shiny copper wire bends easily. Dull sulfur cracks when bent. The definition of metals by the mirror effect does not include malleability. A shiny metal, that cracks before it is bent, is beta-tin. That seems inconsistent with old definitions of metals being ductile. The mirror criterion seems more consistent than the ductility or electrical conductivity criteria to concisely define a metal.

The nucleus is not hidden behind a cloud of electrons. People can directly see nuclei by looking in a mirror. Modern 2026 technology cannot see if my definitions are accurate about the proton direction of reflection. The electron-proton pair is like the Earth-sky relationship. Looking past the Earth and seeing a sky is like seeing a proton. It is so primary that it gets ignored, sometimes. October 12, 2025.

Gas Definition

This is the attempted start for writing a definition of which chemical element is a gas at room temperature. Nitrogen gas is compared to carbon gas. Electron orbital shapes are expected to be more important than nuclear facts, but the Z proton count influences the electrons in the gas phase. All inert gasses from neon to radon are foundation elements. The 19 foundation elements simply have a cube and six pyramids. Two classes of gasses could get two similar definitions.

Inert gas definition: the nucleus is a foundation element and the electron positions…?

Reactive gas definition: H N O F Cl Br, non-metallic cryogenic phase, oxygen is a foundation nucleus, with a cube and six pyramids.

November 1, 2025.

XYZ files for 118 Chemical Elements’ nucleon coordinates

Digital models of the shapes of the nuclei of many chemical elements are available as Blender files. That is a computer aided design (CAD) software tool. The latest file version is named nuclei_118_O.txt . The digital .xyz format files have coordinates of 17,000 protons and neutrons covering all 118 elements. See Tables 1, 2, and 3 to read the numbers of proton rings and the counts of proton line ends. See Table 4 for the vectors for fulcrums for each nuclear bond origin. Those vectors point away from the ends of proton lines, to begin a line of flux, also called a wave function. With the tables, I have enough digital data to build molecular CAD models with the bond visualization theory. Three dimensional models will be made for water and diborane to begin the semi-infinite catalog of potential chemical compounds. Read Ovshinsky‘s ideas about steric hindrance. Also Kehrmann and Whitmore knew about molecular shapes from non-bonding realities of bigger molecules or elements with higher Z, atomic number. See regioselectivity for a chemical concept about this.

Bond Visualization Theory

The motions of electrons near some static nuclear shapes are proposed to use some mechanistic ideas. Quantum ideas are used, sparingly. A durable line of flux goes from each proton to one electron and back again, like a conveyor belt. That is also called a wave function. For chemists, I recommend development of the following theory of bonds. The valences and common oxidation numbers usually have integers with magnitudes from 0 to 8. The nuclei of most elements have numbers 0 to 8 for “the number of ends of proton lines”. That similarity of small integers inspires research to match nuclear shapes to known facts about chemistry. The smallest parts are described next. The durable wavefunctions in molecules join each electron to one proton.

The new theory uses that idea so that most bonds are shown as wrapping lines of flux. That can be visualized as two flat tapes orbiting around each other with the masses of the electrons at the ends of the tapes (Fig. 3). See my first youtube video of a bond mock-up (at time 3:55). That uses ropes as wavefunctions. The video shows two protons in an oxygen nucleus held at the tops of ropes and two electrons freely moving on the bottoms of ropes. At the bottom of the mock-up video, a second oxygen atom is off screen. This is intended to show the O2 molecule, but some mistakes were made in the video narration. The directions of flux wrapping can be anti-bonding or bonding, as is demonstrated before the 8:25 time. The two lines of flux can mesh or clash. (Flux is a wavefunction).

A second youtube video of flux wrapping is here. That uses a flat tape of steel to illustrate the importance of two spins having a relationship that is allowed, or a relationship that is an unfavorable spin polarization of the tape. Two tapes can be flat against each other or they can clash as they have relative twists. For “Electron Spins”, that means a clockwise twist of the flux will prefer to orbit a clockwise twist of a second flux. The second flux orbits the opposite way, so the nomenclature can be justified to have “opposite spins”. A hierarchy of spins has been noticed. The flux converor belt “spin” can have units of meter2/second for the wavefunction. At a larger scale, orbiting electrons go around other orbiting electrons. Their flux gets wrapped up and then it reverses. That can have angular momentum can have units of (meter4/second). Filmed in a Maui, Hawaii forest. In this video, the weight represents an electron on a flat wavefunction that goes to a proton that is off of the top of the screen. The rope represents a wavefunction going from an electron, near the top, to a proton, near the bottom, off screen. From the four particles, only one electron is on-screen. The wavefunctions are on screen for two electrons with opposite spins, that are paired with two unseen protons. The point is that mechanistic ideas can be used for spins, energies, and quantum numbers. The principle quantum number n can be the number of twists on the tape, for example.

The third video is not on youtube, it is here at nuclear-data.com . This is for a lone pair of electrons. That means two protons are at the top of the flat rubber bands and two electron weights are at the bottom of the screen. This is easier for me because it uses gravity to hold both electrons in reasonable locations. (A valence bond is different because one proton is at the top of screen and its electron is at the bottom, but the other proton is at the bottom and the electron would be at the top).

The video 3 shows weights at the bottom representing two electrons. The bands connect the electron to the nucleus at the top, off the screen. The bands have spin highlighted using red stripes or black stripes. That “lone-pair” of electrons does not participate with bonding to another atom, only this one atom is implied in the video.

The oxygen nucleus has a helical shape to its proton allocation. Phosphates in DNA have oxygen in places that put them in the path of the DNA helix. A new model can illustrate the oxygen twist as a possible source of the twisted molecular shape. But does oxygen’s helix always turn clockwise? Maybe there are two oxygen nuclear shapes.

Paper, “Molecular Shapes from Proton Lines”

Water and Diborane

Molecules with light elements allow “pure” insights into primitive facts of atoms. Heavier elements have additional protons interfering with valence bonds, changing their angles.

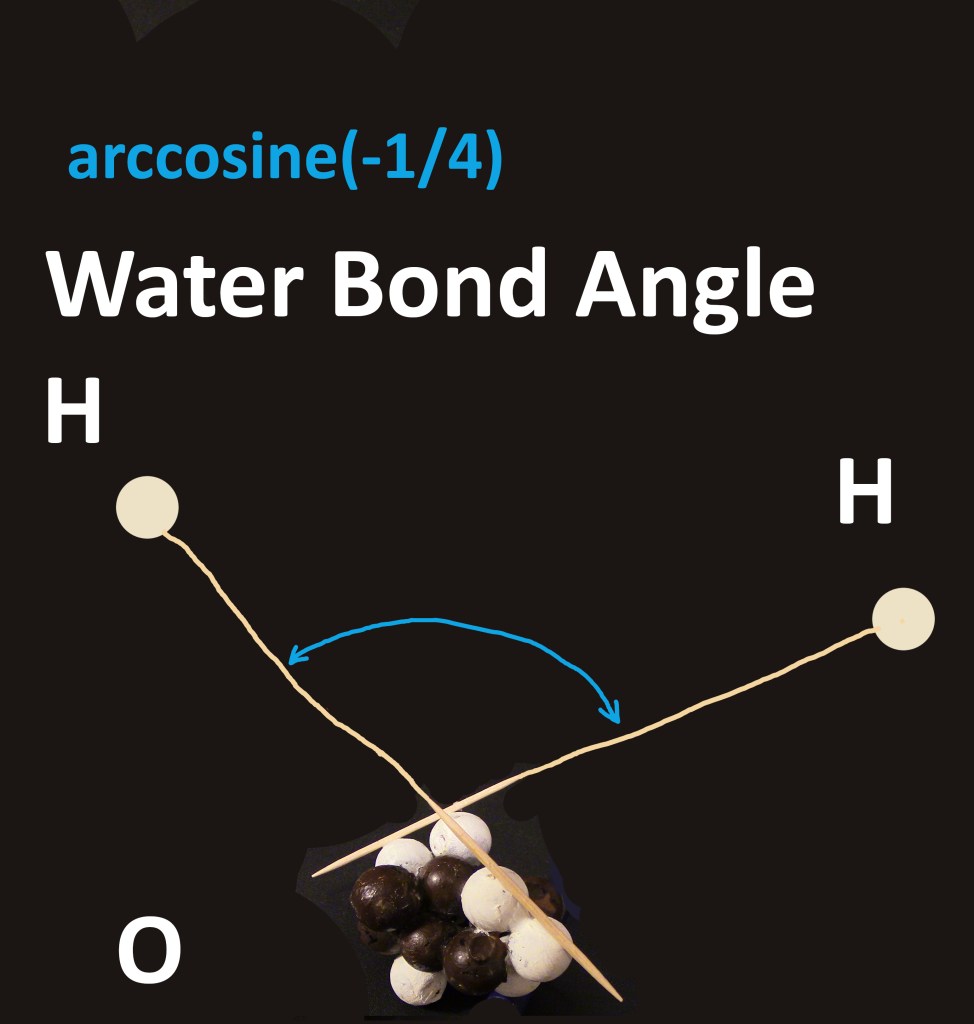

The water bond angle was described in my paper. The cubic lattice of protons and neutrons in the core of oxygen determines the angle of 104.5 degrees [1]. Oxygen is a light element, where bond angles are seen at their purest, without complications found in sulfur. Adjacent proton lines in heavy elements impinge on the wavefunction of a bond, bending it.

angle = arccosine(-1/4) for the Water Bond Angle

Figure 0: Water bond angle from oxygen proton line ends, arccosine (-1/4) due to cubic lattice and stacked, nestled spheres June 1, 2025

Boron is the only element with 5 protons in a straight line.

Figure 1: Boron nucleus with white protons in a straight line

Diborane is a molecule that breaks the chemistry rules of high school. Boron is different from all other elements. B has 5 protons in a straight line. No other element has a long, pure line like boron. Maybe the bond is longer or faster in some internal flow when 5 protons are in a straight line. High school taught me that an element with 5 protons has up to 3 bonds. The 2 s-orbital core electrons do not usually bond with other atoms. My teaching is that carbon is the lightest element with 2 core electrons and a cubic core of nucleons. The cube has 2 protons that pair with 2 electrons. Boron is too light to have a 2x2x2 cube of 2 protons and 6 neutrons. Boron does not have a cube. But boron has six bonds to six atoms of various elements, sometimes. Or nine bonds from one boron atom in a cluster molecule. Boron breaks the simplified rules that educators begin with. Heavier elements make a transition away from 2 core protons to 8 core protons. The electron theory should change to include that transition element phenomenon.

I believe that charge neutrality is a trend. There are equal numbers of electrons and protons in the galaxy, in theory. Molecules teach us through experiments like x-rays or nuclear magnetic resonance, so we make abstractions that deliver ideas about the functionality of subtle phenomena. The orbital abstractions are about energy, not electron positions. The geometries of nuclei now provide new constraints on what mechanistic processes are describable. Algebra tries the alternative to deterministic geometries to use exchanges, dispersion, Coulomb isotropic forces, repulsion, scattering, and non-local factors in equations. Geometry often generates algebraic and efficient approximations to things like 3c-2e bonding in diborane.

Sketches of molecules without using the digital models

Water bond angle sketch is ready.

Figure 2: molecule of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen

Figure 2 shows the oxygen nucleus determining the bond angles with two hydrogens. The 104.5 degree angle was known before this essay [1]. The ends of lines of protons are shown with narrow lines as bonds directed as if a fulcrum is in two protons. The angle can be calculated from Table 4, fulcrum vectors. Protons 8 and 11 determine one vector. The second bond vector is for protons 10 and 16 in oxygen.

Diborane’s proposed molecular theory is ready to show the two electron, three center (2e-3c) standard shape [2]. Boron has two long bonds and three short bonds, in my theory. That is attributed to the idea that a line of protons has two ends. Each end proton can plausibly have a longer bond than a proton in the middle of a line of protons. The long bond overlaps a hydrogen, as if H were an electron! The following sketch shows this original idea. That is the phenomenon that breaks a rule from high school.

Figure 3: B2H6 diborane with bridging hydrogen , 3c-2e, red H atoms

Three atomic centers and two electron orbitals (3c-2e) are used in the diborane molecule, for the two bridges across the center of Fig. 3. The long bond from boron may be due to 5 protons in a pure line. By pure, I mean the 5 protons are not near any other protons and the line is straight. Maybe the boron nucleus has two ends with long bonds, long enough to surround a hydrogen nucleus as easily as an electron.

Page 2 in [2] by Hnyk has written, “three atoms supply three orbitals from each atom. Those three interact to give one bonding and two anti-bonding orbitals. Thus, two available electrons may fill the bonding orbital”. That means that the “3c-2e” symbol is about three atoms and two orbitals occupied by two electrons. The symbol says nothing about charge neutrality, but separately, “electron deficient bonding” is half-described. In this hydrogen bridging piece of a molecule, a boron atom treats a hydrogen nucleus like an electron. That proton is bypassed and enveloped by the flux from B, the way an electron and its flux bypass another electron and tangle to make a bond.

The boron bond with the hydrogen bridge can be described partly as a mechanical tangling, and for some aspects, as a quantum theory like Dirac’s. Two lines of flux wrap around each other mechanically. An energy and angular momentum of a springy tape model can be calculated and adjusted to match the old values. Quantum integers can be mapped from mechanical items, like tape twist direction to be mapped to spin, and the number of windings between two lines as the principle quantum number n. A local coordinate system is used in each proton-electron pair. The boron line of flux uses the hydrogen nucleus mechanically, as it would any electron, regardless of the + or – charge polarity. That effect can add to the quantum-only explanations. Directions and geometries are essential to the combined quantum and classical model. That aspect has been disregarded so discrete electrons and protons can be treated as if they are not “paired”.

Tour of diborane using coordinates in Fig. 2

This essay starts at the top left of Fig. 3, like reading three sentences from left to right. The tour begins with hydrogens bonding to borons. Then a sentence for two lone electrons near the cores of the two boron nuclei. The last sentence from left to right is again about hydrogens bonding to borons. 16 electrons are shown with 16 protons and 12 neutrons. The (x, y) coordinates are around the figure.

(1, 3) A hydrogen nucleus emits a red line of flux towards the bond wrapping sketch. The red flux wraps around a black flux from a boron nucleus. That is like two steel tapes getting tangled in a way that is favorable for untangling. The flux’ springiness and flatness are like from a tape-measure product.

(5, 3) The two wavefunctions orbit each other and then unwrap to orbit the other way. The electron masses orbit the lines of flux so energy can be calculated for that orbital. Quantum numbers can be assigned from the wrapping to represent standard symbols (n, l, ml, ms).

(13, 5) The boron nucleus.

(21, 13) The bridging hydrogen atom. A red line of flux is emitted the second boron nucleus. A black line of flux from the first boron bypasses the hydrogen nucleus and intercepts the red H line. That is a bridge-type shape that encompasses a hydrogen nucleus in an unusual way.

(26, 4) The electron from the first boron has wrapped its long black line around the red flux to create the bond. Boron has some long bonds and short. Also, the red line continues to the right beyond that electron to wrap around a second line of flux from the second boron.

(30, 4) The red line ends at an electron attached to the bridging hydrogen atom. That red line is wrapped around a black line from the second boron atom. The red hydrogen atom is wrapping its line around two different boron atoms.

Before moving to Fig. 3 middle section, some questions and ideas.

Questionable notes about boron

first: electron deficient bonding in boron literature?

second: 3c-2e counting electrons where? The three orbitals are two anti-bonding and one orbital bonding. 2e fill the bonding orbital. (2e means two electrons and 3c means three centers, atoms).

third: protons are 5, but 6 bonds in closo BH cluster? 7, 8?

Maybe the electron at (32, 8) makes a “lone pair” with the H electron at (30, 4). That would justify the 3c, 2e name. That implies 2 electrons, but 3 are really there. That lone pair would be “hidden” from bonding diagrams, like in standard lone pairs. The book on boron does not address these aspects. It treats “orbitals” being made by several atoms as more important for counting electrons than the number4 of protons. Since that is their attitude, then sure, 9 bonds to 9 atoms using 5 protons in boron.

(10, 6) The electron is attached to the core of boron. In B2H6, there are no two s electrons in a core orbital. Maybe we can see that electron as uniquely positioned, without being in a lone pair.

(32, 8) An electron from the core of boron. It seems to never be mentioned in the book by editor Hnyk [2]. His figures show a boron with 4 bonds, but 5 protons. The book does mention “electron deficient bonding”. This may be the missing electron at these coordinates.

(2, 9) The last row of this essay is like the first row, already described.

References in Chemistry

[1] Fundamentals of Molecular Spectroscopy (2023), Prabal Kumar Mallick, page 217 for the bond angles, ISBN 978-981-99-0790-8

[2] Boron The Fifth Element (2015), edited by Drahomir Hnyk and Michael McKee, see scheme 2.1 for the bridged bond, 3 atoms and 2 orbitals, ISBN 978-3-319-22281-3

January 9, 2025

Leave a comment